The origins of this edition lie in the Biblia Polyglotta Matritensia project, an ambitious initiative launched by the former Instituto Arias Montano of the CSIC to produce a new polyglot Bible. The initial plan was to use the Leningrad Codex (B19a) as the primary Hebrew text, together with its Masoras and a critical apparatus. This apparatus was intended to include Masoretic sources (Sefer Diqduqe ha-Teʿamîm, Sefer ʾOklah we-ʾOklah, the Treatise of Mishael ben Uzziel, the differences between Ben Asher and Ben Naftali, the Hillufim, etc.), extra-Masoretic sources (Talmudic and Midrashic variants, the Samaritan Pentateuch, the Dead Sea Scrolls), Babylonian and Tiberian variants from the Cairo Genizah fragments, and non-Hebraic sources such as the ancient versions.

However, the project to edit the Hebrew text underwent several transformations, as various references attest, eventually evolving into a distinct endeavor. In 1961, during the Third World Congress of Jewish Studies in Jerusalem, Pérez Castro announced that the Cairo Codex and its Masoras would serve as the basis for the Spanish edition. This revised project would also incorporate variants from the Aleppo and Leningrad texts and their Masoras, alongside Masoretic treatises such as Sefer Diqduqe ha-Teʿamîm, Sefer ʾOklah we-ʾOklah, and the Treatise of Mishael ben Uzziel.

It was not until the 1970s that the project assumed its definitive shape. A new generation of scholars redefined its scope, culminating in the decision to focus exclusively on the Cairo Codex. Emilia Fernández Tejero played a pivotal role in this shift, persuading Pérez Castro that the Hebrew team should dedicate itself solely to the publication of the Cairo Codex of the Prophets and its Masoras. This decision marked the beginning of the work that ultimately led to the edition we know today.

The evolution of the project can be traced through several documents reflecting its different stages: the section of the Prooemium (1957) 1 corresponding to the Hebrew text; the original, unpublished version of Pérez Castro’s paper presented at the Third World Congress of Jewish Studies (Jerusalem, 1961); an internal “white paper” outlining a detailed plan for the edition; and finally, the paper delivered at the founding congress of the IOMS (Los Angeles, 1972), titled “A Diachronic Edition of the Hebrew Old Testament.”

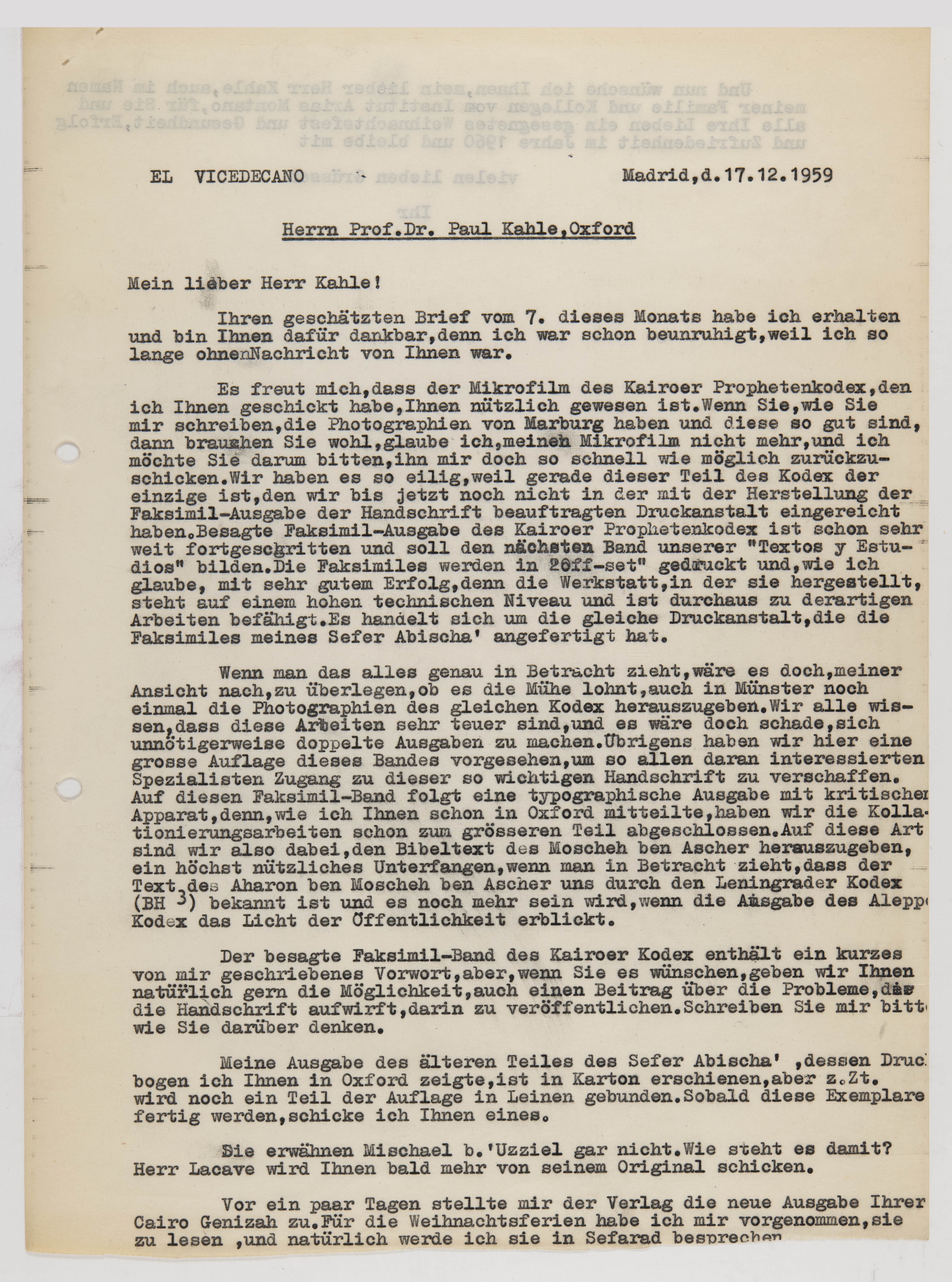

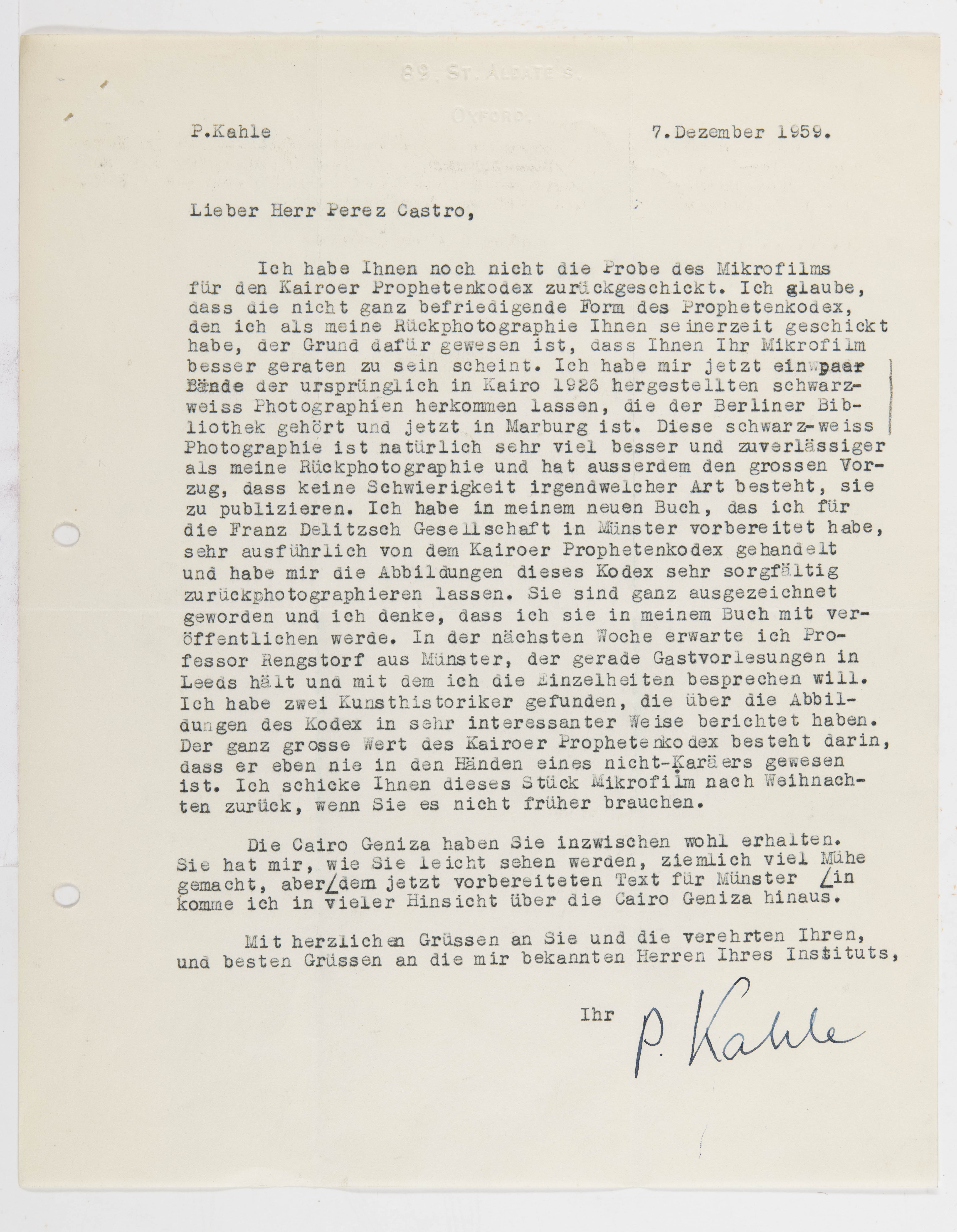

The correspondence between Paul Kahle and Federico Perez Castro sheds light on the preliminary stages of the edition of the Cairo Codex of the Prophets. In December 1959, they exchanged several letters concerning the essential materials required for the edition: microfilms and photographs (Figs. 1 and 2).

Kahle initially sent inverted microfilms of the codex to Madrid, which required the Spanish team to use mirrors to read the text. Later, through Kahle’s efforts and with the assistance of the Bonn Orientalisches Seminar, black-and-white photographs of the Cairo Codex were obtained and made available to Pérez Castro.

Despite the clarity of these photographs, the editorial team deemed it necessary to examine the original manuscript to resolve ambiguities encountered during the initial collation. Notes from the collation notebooks reveal that most uncertainties concerned vowel and cantillation signs. In some cases, signs such as dagesh and raphe were unclear; in others, the vocalization of entire sentences or paragraphs required verification.

In February 1976, the team began efforts to gain access to the Karaite Synagogue in Cairo, where the codex was housed. After two years of negotiations, they received an official letter of confirmation signed by Mr. Massouda, president of the Karaite community, on January 13, 1978. On May 3, 1978, Prof. Emilia Fernández Tejero and María Teresa Ortega Monasterio traveled to Cairo (Fig. 3). Over three weeks, they worked meticulously on the manuscript, resolving the team’s doubts concerning each book. They recorded every detail of the codex, noting scrapings and erasures, the exact placement of signs, and revising the vocalization of extant portions of the text. Moreover, they examined other manuscripts held in the synagogue, such as Gottheil 14, 17, and 18.”

The publication of El Códice de Profetas de El Cairo spanned nearly two decades, beginning with Tomo VII: Profetas Menores, which appeared in 1979. This first volume also included the Prefacio, a justification of the edition and an explanation of its structure and character. The subsequent volumes were released in the chronological order of the biblical books: Tomo I: Josué–Jueces (1980), Tomo II: Samuel (1983), Tomo III: Reyes (1984), Tomo IV: Isaías (1986), Tomo V: Jeremías (1987), and Tomo VI: Ezequiel (1988), these volumes completed the series of seven volumes dedicated to the biblical text. In 1992, Tomo VIII, an alphabetical index to the Masora parva and Masora magna annotations, was published. Between 1995 and 1997, additional complementary volumes were issued, including analytical indices of the Masora magna and Masora parva, as well as studies on the occurrences of let (‘unique’) cases.

Although the edition is often attributed to Federico Pérez Castro, it was primarily the result of collaborative work. For this reason, Pérez Castro appears in the volumes as director rather than sole author.

The editorial team included:

• Carmen Muñoz Abad

• Emilia Fernández Tejero

• María Teresa Ortega Monasterio

• María Josefa Azcárraga Servert (from Volume II onward)

• Eugenio Carrero Rodríguez (Volumes I and VII)

• Luis-Fernando Girón Blanc (Volume VII)

In addition to their editorial contributions, specific responsibilities were assigned: Emilia Fernández Tejero was responsible for the analytical index of the Masora magna, María Josefa Azcárraga Servert for the analytical index of the Masora parva, and María Teresa Ortega Monasterio was responsible for the index of the let cases.

The edition comprises the biblical text, two apparatuses and explanatory notes (Fig. 4).

The biblical text is reproduced in a single column—rather than the three-column layout of the manuscript—while preserving the division of the parashiyyot (sections of the Torah read publicly in the synagogue). Lines where the last word exceeds or falls short of the established margin are completed with the letter mem (מ). Additionally, the edition reproduces the circellus, a small circle placed over a word or words in the biblical text to indicate an associated annotation in the manuscript’s margins (see Apparatus II).

The first apparatus compiles words with uncertain spellings due to manuscript deterioration or punctuation inconsistencies, providing commentary on these cases. Each lemma is presented only with the punctuation relevant to the discussion.

The second apparatus records the transcription and development of Masora Parva and Masora Magna annotations and identifies the simanim (a selection of one or more words from the affected verses). The Masoretic annotations are reproduced as they appear in the manuscript, except where the indicative period for abbreviations and technical terms is missing; in such cases, it has been supplied.

When both Masora Magna and Masora Parva annotations coincide for the same lemma, the Mara Parva is not reproduced, and the coincidence is indicated by the symbol =. Superscript letters in this apparatus refer to explanatory notes at the bottom of the page, where certain annotations are clarified or expanded.

The edition of the Cairo Codex of the Prophets represents a landmark achievement in the field of biblical scholarship. It introduced several key innovations that distinguish it from previous editions:

Another significant, though often overlooked, innovation was the comprehensive indexing of the Masora—a pioneering effort long before the advent of digital search tools. Volume VIII contains an alphabetical index of the Masora Magna and Masora Parva annotations of the Cairo Codex, while two additional volumes provide analytical indexes of both Masoras. These tools revolutionized access to Masoretic annotations, enabling scholars to locate and study every annotated word in the Cairo Codex with unprecedented ease.

As María Teresa Ortega Monasterio, a member of the editorial team, stated:

Finally, the Cairo edition stands out as a hybrid work—half printed, half manuscript—offering an unparalleled level of precision. Due to the technical limitations of the time, the consonantal text was typewritten, while vowel signs and accents were added manually. This painstaking process ensured an exact reproduction of the manuscript’s palaeographic features, preserving details often lost in critical editions. Among these are: the precise placement of gaʿya, raphe, and meteg signs; the distinctive shapes of accents such as pazer and zarqa; the exact layout of poetic texts, including the Song of Deborah (Judg 5:2–31) (Figs. 5 and 5bis); characteristic ligatures, such as aleph-lamed (Figs. 6 and 6bis); and the unique form of qames in this manuscript—rendered as a horizontal line with a point below (Figs. 7 and 7bis).

Described as "a masterpiece of reproduction" (Dotan, “The Cairo Codex,” p. 170), this edition not only preserves the textual integrity of the Cairo Codex but also provides valuable paleographic insights rarely found in other Hebrew Bible editions.

The edition of El códice de Profetas de El Cairo stands as a landmark achievement in biblical studies, both for its scholarly precision and its significant contribution to Masoretic research. The dedication and expertise of the Biblia Hebrea team have been widely recognized in academic circles, as evidenced by numerous reviews and studies.

Prominent scholars have highlighted Spain's leading role in Masoretic studies thanks to this work. Professor H. M. Orlinsky stated:

Similarly, Pierre-Maurice Bogaert emphasized the international reputation of the team:

The edition’s scholarly relevance and necessity were also underlined by Emanuel Tov, who noted:

Beyond its importance as a primary resource, the precision and accuracy of the edition have been universally praised:

Dotan further emphasized the groundbreaking nature of this work:

Moreover, Dotan underscored the unparalleled role of the Madrid research team in Masoretic studies:

In short, this edition remains an essential and irreplaceable tool for scholars dedicated to the study of the Hebrew Bible

Ayuso Marazuela, Teófilo, et al. Biblia polyglotta matritensia / Cura et studio Ayuso T. Bellet P. Bover, J.M. Cantera, F. Diez Macho A., Fernández-Galiano M., Millás Vallicrosa J.M., O’Callaghan J. Ortiz de Urbina J. Pérez Castro F. aliisque plurimis collaborantibus peritis. [La Editorial Católica], 1957.

Recommended citation: Martín-Contreras, Elvira and Biblioteca Tomás Navarro Tomás. The Cairo Codex of the Prophets: digital edition. [online] https://biblioteca.cchs.csic.es/Codice-Profetas-Cairo/ [date of access]